The power of a dream and the simplicity of elegance, the timeless charm of Brazilian Modernist architecture past and present

When architecture is human expression, when it represents an inner feeling, when it designs a poetic vision of the world in which we live, it becomes art capable of shaping the space and lives of the people living in it.

Author: Gaia De Santis

Drawings: Maurizio Faleschini

Tagged as: Stories, Inspirations

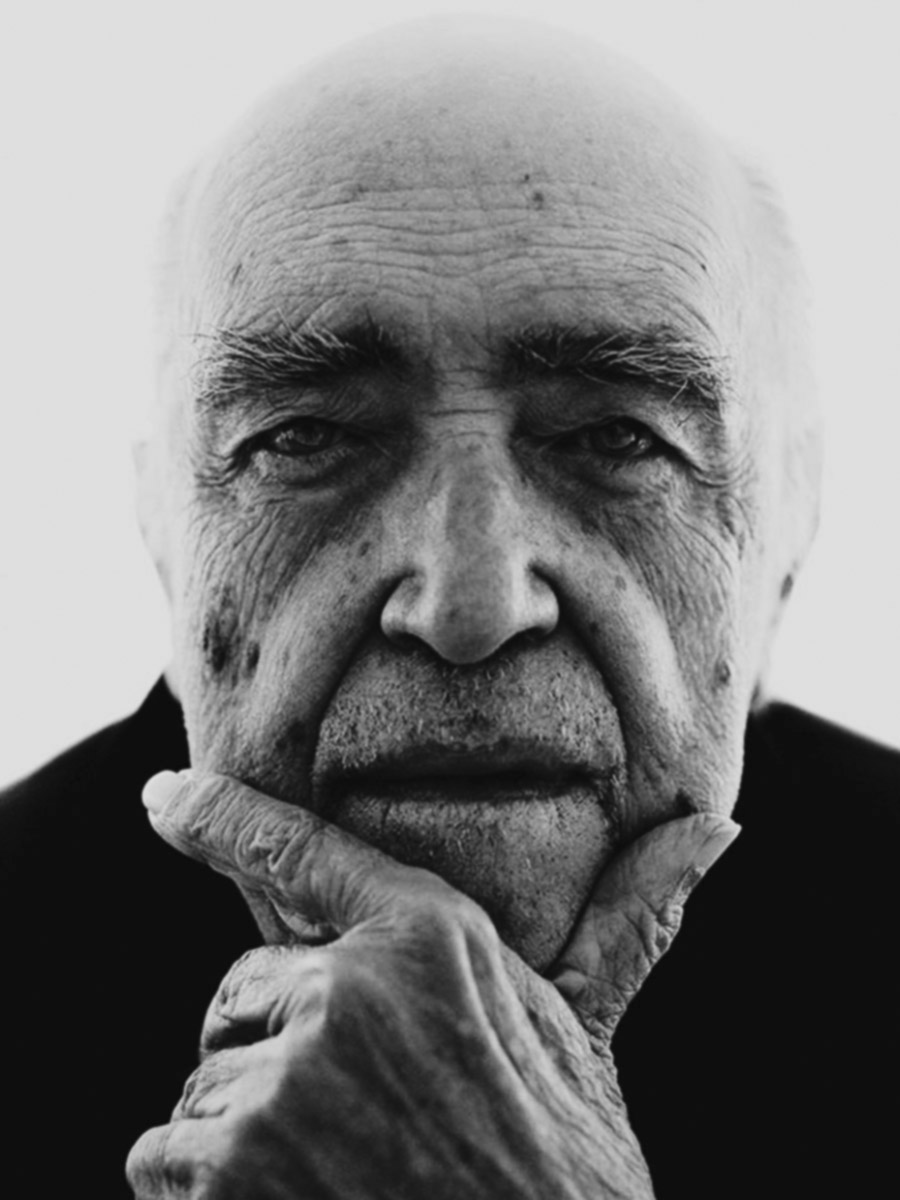

Portrait of Oscar Ribeiro de Almeida de Niemeyer Soares, commonly known as Oscar Niemeyer, the great architect of Rio de Janeiro, who designed some of the most famous modernist buildings of the twentieth century.

Brazilian Modernist architecture reminds us how important it is for us to dream, to look upwards and search for the light between the full and empty spaces of aerial shapes that render perspective infinite. Oscar Niemeyer as a young man worked with Lucio Costa and Le Corbusier and was acknowledged internationally as the undisputed master of Brazilian Modernism from the ’50s onwards. Winner of the Pritzker Prize (the Nobel prize for architecture) in 1988, the Leone d’Oro at the 1996 Venice Biennale and the Praemium Imperiale for architecture in 2004, he continued until the very end of his long career to carry out extensive research into the architectural roots of his country, Brazil. He elaborated a sort of architectural lyricism represented by new shapes that were almost sculptural in style, recreating the fluidity of nature and its most spectacular identity.

Federal Supreme Court of Brazil in Brasilia, Oscar Niemeyer

Niemeyer said “I am not attracted to straight angles or to the straight line, hard and inflexible, created by man. I am attracted to free-flowing, sensual curves. The curves that I find in the mountains of my country, in the sinuousness of its rivers, in the waves of the ocean, and on the body of the beloved woman. Curves make up the entire Universe.” Modernism is a new, sleek, inebriating concept in architecture, which delves into the origins of things and shapes and the way they manifest to man, who cannot help but be inspired by them. A prime example of this vision, one of Niemeyer’s many famous works, is the project for Brazil’s new capital city, Brasilia, which brings together some of the Brazilian architect’s greatest masterpieces, constructed in partnership with Lucio Costa, Roberto Burble Marx for the landscape design, Joaquim Tenreiro and Martin Eisler, who custom designed much of the furniture. Joaquim Tenreiro, Portuguese by birth but Brazilian by adoption, was considered the father of Brazilian Modernist design. He centred the design of his furniture upon the excellence of the Brazilian manufacturing tradition, paying special attention to the use of certain hardwoods, a material that Tenreiro, who came from a family of traditional carpenters, was very fond of. A sculptor, painter and artist, he shared a great understanding of Niemeyer’s concept of modern interior design in the ’50s. Martin Eisler, a Viennese architect who fled from Nazi Europe, found in Latin America the enthusiasm, dynamism and energy that enabled him to express an innovative creative concept. He was inspired by and an accomplice of Niemeyer’s Modernist principles and the cultural buzz that expressed through design a wonder for life, relations with others, love for the environment, in one of the most fortunate intellectual unisons in the history of architecture. In Niemeyer’s own words, referring to the studio’s work, “The architecture we propose is invention. We don’t limit ourselves to controlling space solely as a means of creating functional forms. I say that architecture is invention, it’s a machine the purpose of which is to create surprise. […] Our architecture borders on the fields of art, painting, sculpture: this means that we are still capable of developing projects that create surprise, that express wonder and that are always amazing. […] The fundamentals of a work of art are the emotion and surprise it generates. We would like to achieve the same effect through architecture.”

Brazilian Foreign Office in Brasilia, Oscar Niemeyer

The visionary works and Brazilian design pieces that are still famous today, such as the Costela and Reversível armchairs by Eisler, re-edited by Tacchini Italia Forniture, are timeless examples of a philosophy rooted in architecture, which photograph in a building or piece of furniture the intelligent, poetic fervour of men who ingeniously compared their thoughts and deeds to offer the eye and mind new perspectives and new solutions. This teaching has been inherited today by contemporary architects such as Marcio Kogan, an honorary member of the American Institute of Architects, Brazil’s representative at the 2012 Biennale in Venice and winner of over two hundred national and international awards, from whom the Tacchini Italia Forniture installation for the 2019 Salone Internazionale del Mobile in Milan draws its inspiration. And by designers who are currently leaders in their fields, such as Zanini de Zanine, son of architect and designer José Zanine Caldas, who designed the highly unusual Lagoa for Tacchini Italia at 2019 Salone; Italo-Brazilian designer, Giorgio Bonaguro, who found inspiration for his latest collection of Joaquim coffee tables from the works of Joaquim Tenreiro. These play tribute to the principle of lightness that the Modernist designer theorised as being fundamental for the production of modern Brazilian furniture. Lightness not intended in terms of physical weight but in terms of the grace and functionality of an object in space.

Today, as in the past, the creativity of Brazilian architects and designers conveys the value of imagination, the power of a dream, which goes beyond mere function. The sensuality of smooth, natural curves and dialogue with nature and the environment outside of ourselves in materials, shapes and harmonious design that always looks at the whole and never the individual element. Marcio Kogan, in his gratitude for Niemeyer and Lina Bo Bardi’s modernist teachings, believes in “the idea of improving and changing things using simplicity, gentleness and elegance”. Elegance becomes a principle of his vision. Perhaps because in its most sincere manifestation, it is the perfect representation of natural beauty, beauty that is intrinsic in simplicity. Oscar Niemeyer continued to work until his death in 2012, days before his 105th birthday, in his studio, an attic on the top floor of a building facing out over Copacabana beach. He had a grand piano placed in the centre of the main hall, built in the form of a long wave around a glass façade facing out over the horizon, which was played during the cultural study breaks. He also used to organise regular meetings with a professor in his study that anyone could attend, to talk about philosophy and the cosmos, and to edit an architecture magazine for young people. He conceived architecture and design as a form of culture to be placed at the service of life, people and their existence in the world, to make it as authentic, intense and beautiful as possible because, as Niemeyer himself said “life is more important than architecture.”

A design culture, a beauty culture, the values that the savoir-faire of Tacchini Italia Forniture is committed to everyday. Citing a line from a historic piece by Gilberto Gil, a famous musician and singer, and Brazil’s former Minister of Culture: “Louvando o que bem merece”.

Prev

Prev